Ben Troen and Charlotte Powning

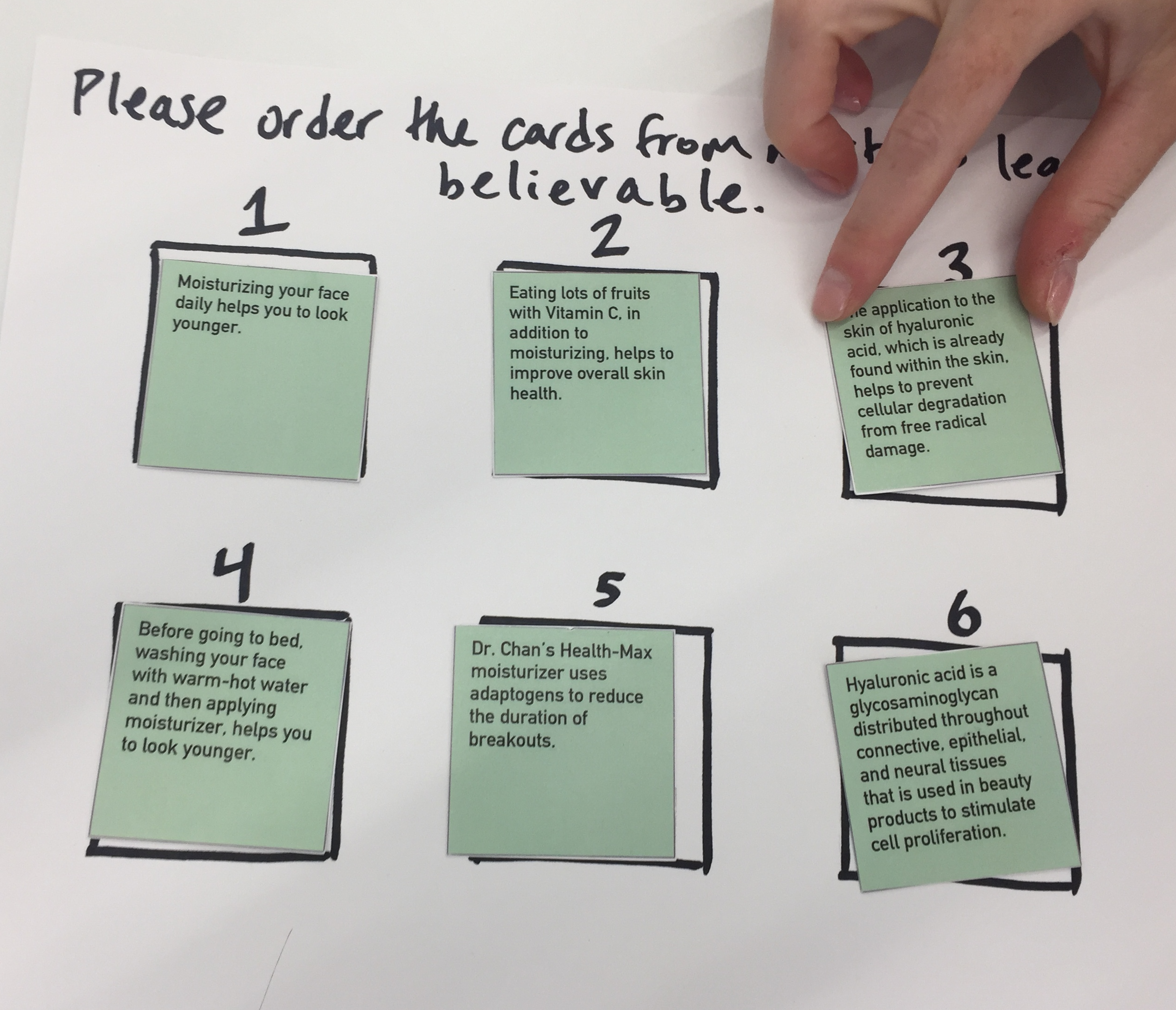

Participants were asked to order the trustworthiness of statements regarding the three medically-adjacent contexts: beauty, fitness, and play.

A new gauge to the behind-the-wheel dashboard, which shows drivers how much carbon dioxide and nitrous oxides their driving is releasing into the atmosphere.

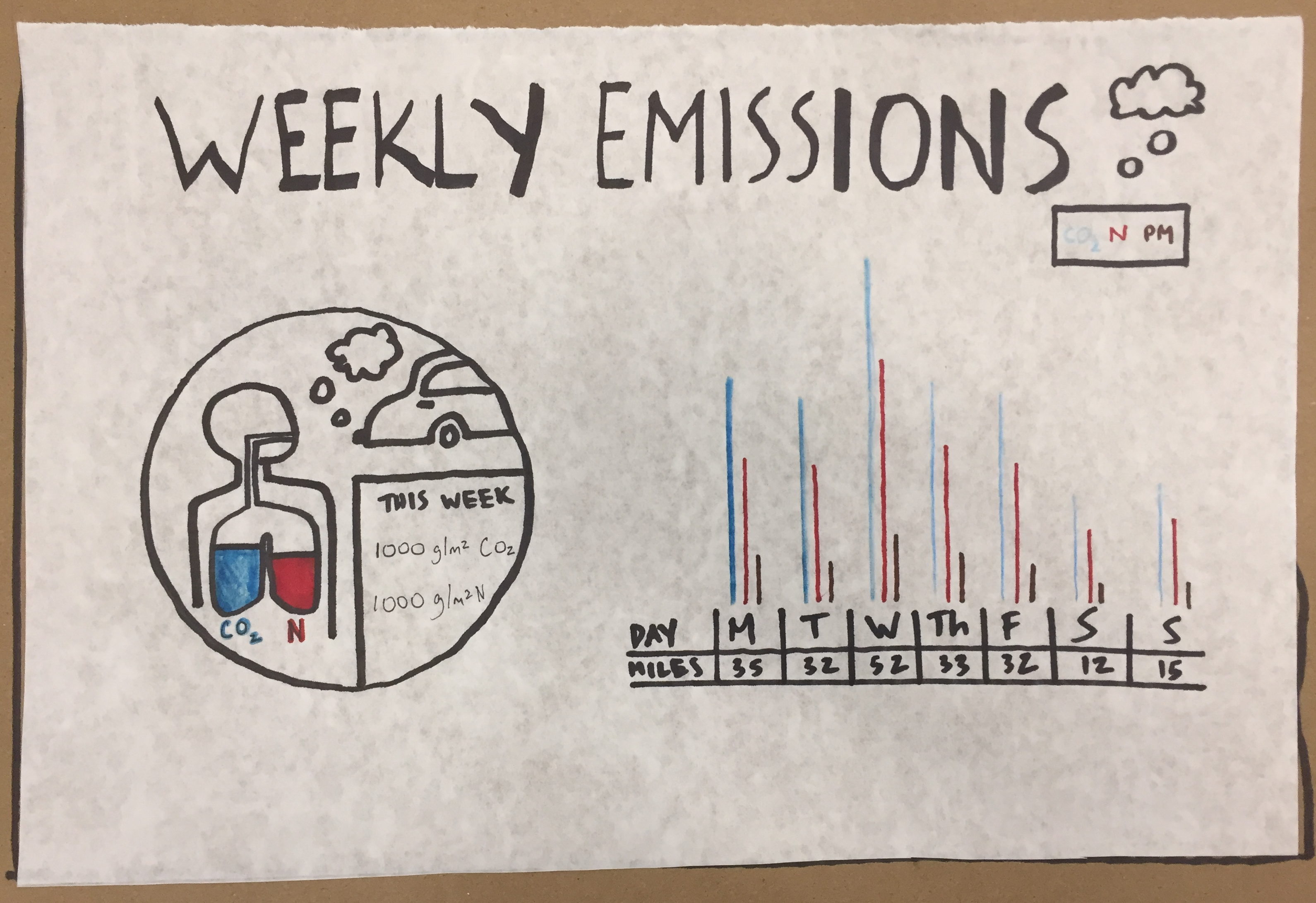

Located in drivers' garages, this intervention communicates with the car dashboard emission information and displays cumulative data.

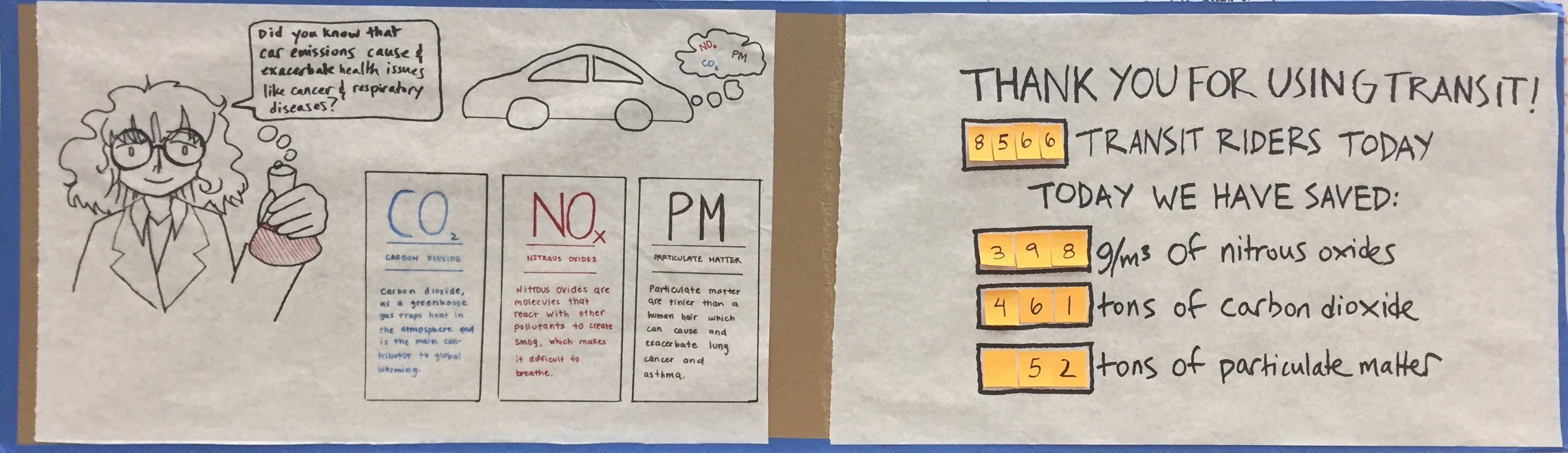

A billboard found at transit stations relaying both the science of air pollution and passengers' effect on emissions.

How can we evaluate and leverage trust in science?

We encounter scientific discourse and methods all around us from our beauty products to political economy. However, too often science can be confusing or worse, intentionally misleading.

This is a pertinent question in a world where too many don’t acknowledge the science of vaccines or the urgency of anthropogenic climate change, both of which are acute.

We sliced off a portion of this greater problem and focused our efforts on air pollution, particularly on dangerous air contaminants. According to the World Health Organization, 7 million people a year die from air pollution and ~80,000 of those are in the United States. Can science communication have an impact on the respiratory health issues caused by air pollution?

To begin tackling this problem we explored the trustworthiness of science in beauty, fitness, and play, which are medically adjacent contexts, meaning areas pertaining to health, but outside the clinical realm.

For our evaluation we created an entirely unscientific BS-ometer to document the level of trust we experienced with certain statements or ideas. The analysis of this data enabled preliminary hypotheses regarding the principles of trust, which we further studied with a card game that we used to engage a larger samping of people outside our design team.

We learned that there are six principles that affect participants’ levels of trust. The first three are whether the statements contain a balance of specific and general information, if the person communicating the science has authority or personal relationship to the recipient, and lastly whether the type of science matches the material, spatial, or larger informational context. The latter three are checks that participants undertook: whether the information matches with their personal experience, if it is perceived as common sense and or general knowledge, and lastly whether or not the specific language matches their internal scientific dictionary.

We proposed a suite of interventions along the scales of time and size within the domain of transit, which is one of the largest contributors of CO2, nitrous oxides, and particulate matter, all harmful to respiratory health. The gauge of nitrous oxides and carbon dioxide in the car dash syncs with the garage screen to provide cumulative data. These build on existing experiences and contexts, while conferring information that is not only tied to daily habits, but largely familiar from high school science. On a large scale, we proposed a billboard with live-updating ridership information that in turn communicates the total saved pollutant emissions. Additionally, we envisioned a concise, but balanced educational component communicated by a scientist to supplant internal dictionaries.

Together these interventions are the beginnings of an infrastructure that utilizes the six principles of trust to successfully communicate the science of air pollution, and its health and environmental pertinence. By spanning multiple scales, and the personal and public spheres, we are increasing the opportunity for personal confrontation of air pollution in daily life. We hope the resulting improved scientific literacy surrounding these issues reduces automobile usage in favor of public transit. More so, we hope that by creating a ubiquitous discourse, we can jumpstart action on harder-to-impact portions of our lives, like governance, which can help implement more lasting change.